Several years ago, I randomly came across an interesting piece published by Professor Marco Piras (Meggen, Luzern March 2006) on the web, of which I report below some significant excerpts:

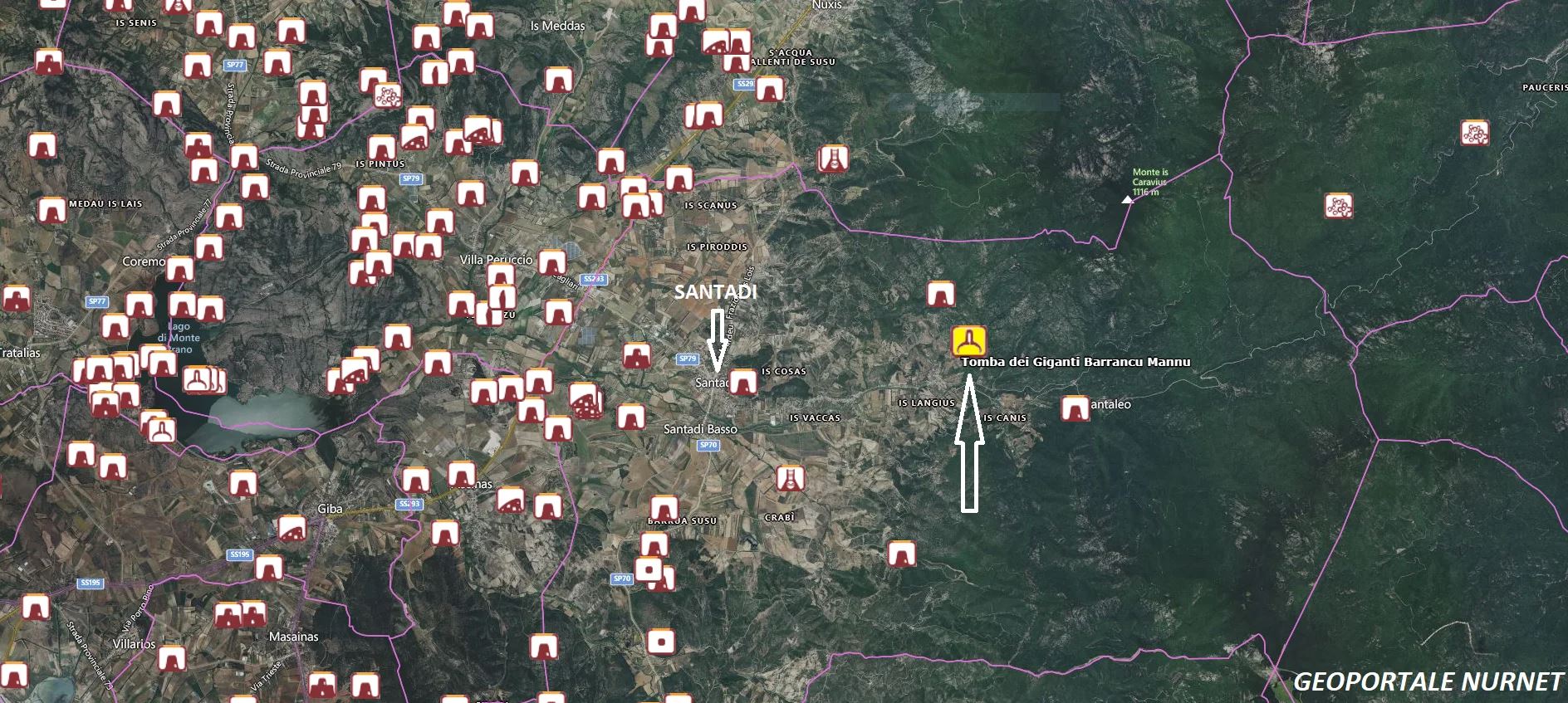

“While preparing lessons for a Master’s program at the University of Cagliari and re-listening to tapes I recorded during a survey conducted in 1984 in the Sulcis area, I stumbled upon an interview with a 96-year-old man from Santadi. Furthermore, this very brief interview, which I had never used for my phonetic and phonological studies due to the poor sound quality, both because the elderly man’s pronunciation was terrible and because the interviewee did not always respond appropriately. Consequently, I limited myself to conducting a free discussion on what he liked, and among other things, he enthusiastically listed insults, curses, invectives, etc. Among the numerous varieties regarding “su cunnu” that he had recounted and that are partially mentioned above, one completely escaped me and at the time did not evidently strike me, perhaps precisely because of the little attention I had paid to this informant and the little attention my research paid to the lexical aspect. Torradìnc in su cunn (..) perda. The poor quality of the recording and the pronunciation, moreover obscured by a throat clearing, could support a rendering as torradìnc in su cunn and pèrda, “return to the stone vagina.” But one could also hear a Torradinci in su cunn e sa perda (return to the vagina of the stone). Even the listening proposed to other phonetics friends did not provide other possible decipherments. After some time, while reflecting on Gimbutas’s beautiful publication, I was suddenly struck by a fantasy, or rather an association of ideas. “What if the possible stone vagina (assuming I correctly deciphered the old man’s phrase) were the domu de janas or the tomb of the giants, or both? At the first opportunity I had to return to Sardinia, although I did not expect to find my informant still alive after 20 years, I wanted to try, through direct and indirect questions, to confirm my supposition. I found the only living son of my informant, more than eighty years old, unfortunately not very present, deaf, and with severe articulatory difficulties. I wanted him to list the invectives in which the word cunnu appeared that he knew, but in the meantime, I couldn’t make him understand what I wanted, and in any case, it was almost torture to make him speak. I had no choice but to proceed with direct references to the invective heard from his father’s voice, and so I played for him at full volume the part where his father spoke of “su cunn ‘e sa pèrda” if that was how it was to be understood. I asked him if he knew the expression su cunn ‘e ssa pèrda. Methodologically, this is not very correct, but the informant’s condition did not allow for anything else. He nodded. I repeated in Sardinian: your father said “su cunn’e sa perda,” have you ever heard it?” He kept nodding. I asked him “what is su cunn e sa perda?”. The person hinted at a distant place but could not explain more. The son, who was disinterestedly observing the conversation, almost annoyed because he was waiting for me to leave so he could finally take care of something, told me that I wouldn’t get anything out of it and made me understand that, poor thing, his father was not entirely in his senses “Léi ca non di òga suppa,” “Badi che non ne cava nulla.” But, upon my insistence, and with the help of this son, I understood that the old man wanted to take me to some point in the countryside. With my car, indicating to me, when necessary, where to go, we arrived at the fraction of Terresòli and at the foot of a hill, at a point where we could not proceed by car, he indicated a direction. The man was unable to take more than a few steps. Therefore, it was impossible to be guided. I got nothing more out of it. But, in fact, in that direction is the location “Barràncu mannu” where there is a tomb of the giants. After obtaining a Polaroid, the next day I photographed the tomb of the giants and returned to the informant who, evidently, still had enough sight to recognize the object, and to my question if that was su cunn’e sa perda he answered with conviction, yes. All this is not considered absolutely conclusive. It is certain that it should be a stimulus for researchers to investigate in this sense, in other parts of Sardinia, both concerning the linguistic aspect and anthropology in general. g.v.

The photos of the tomb of giants of Barrancu Mannu are by: Nicola Castangia, Giovanni Sotgiu, Bibi Pinna, Marco Cocco, Sergio Melis, and R.S.