The following excerpt, titled “The nuraghi of Gorropu and Mereu – The cult of waters,” is taken from the guide “Sentiero Sardegna,” published by Salvatore Dedola in 2001 (Carlo Delfino Editore).

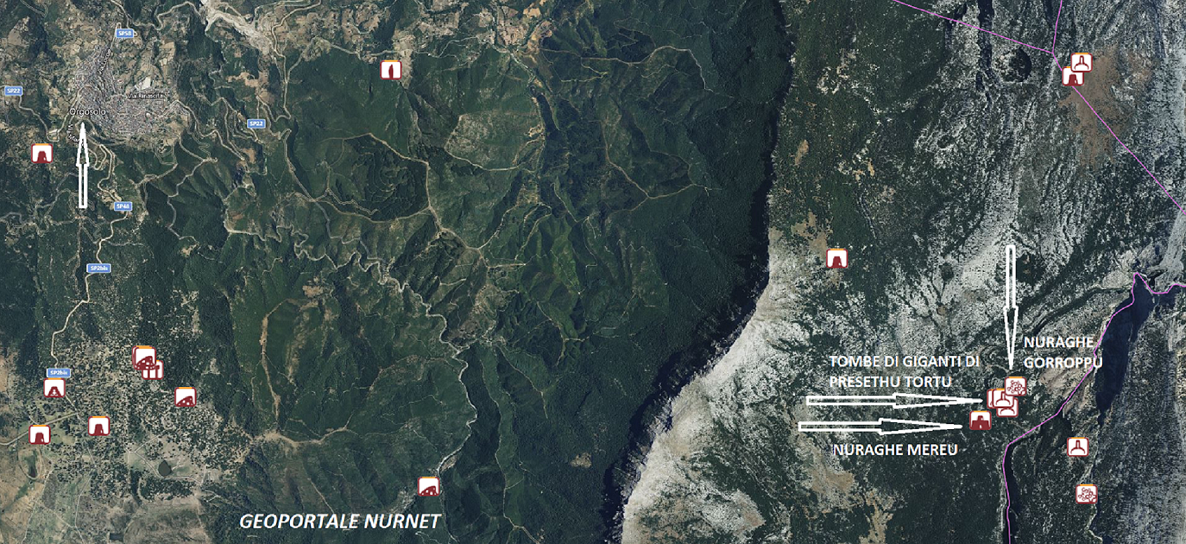

“The sheepfold is the furthest from the village: it nestles in the heart of the Supramonte guarding the steep sinkhole basin of Pischina Gurthàddala, above Gorropu. At the site of the sheepfold, there was a nuragic village, whose ruins are still visible along with the tomb of the giants located in the wide meadow beneath the sheepfold, on the edge of which grows the largest and most beautiful Taxus baccata in Sardinia for millennia. This tree is an authentic natural monument, which forms a trio with the tomb and the village, monuments that mark human presence dating back 4000 years. The unique site of the village mirrors the equally unique site of the nuragic village of Presethu Tortu, located opposite across the deep gorge of the Flumineddu, which presumably separated two tribes. Perhaps the division was only territorial, not political, because the two nuraghi of Presethu Tortu (Mereu and Gorropu) raise doubts about improbable guarding functions, as they too are oriented – like the village of Sedda Arbaccas – towards the gigantic tectonic “funnel” of Gorropu (an impenetrable gorge from below) onto which converge – as we mentioned elsewhere – three gorges with hostile, impassable bottoms, not least because of the presence of towering smooth cliffs that interrupt its accessibility. The village of Presethu Tortu has disappeared, returning a myriad of stones to nature, but the two nuraghi, only 800 m apart, still stand tall and are still recognizable. They were nothing more than a fortified dwelling of the local “king” (at Mereu) and a large altar-sanctuary incorporated in a wide rectangular courtyard (at Gorropu). On these cliffs, the same functions reappear as those of the nuragic sanctuary of Serri and the ancient nuragic site of Santu Bantine di Sedilo, an open “Mecca” for pilgrims 3-4000 years ago. The meadows of Presethu Tortu undoubtedly attracted pilgrims from all over the Supramonte: from the passes of Gantinarvu, Solitta, Janna ’e Gori, Punta Gruttas, Sìlana; from the villages of Sòvana, Giulia, and Duavidda. It was a periodic gathering towards the plain of Campu Mudrecu-Su Disterru, bordered by the nuraghe and the nuraghe-sanctuary of Presethu Tortu which, down below, watched the waters converge into a triangle, an ineffable Trinitarian spectacle whose grandeur brought one closer to God. The cult of waters was very strong in Sardinia. From one of the three gorges, bordered by the dizzying walls of Cucuttos, a copious waterfall sprang (and still springs) from a large vertical crack, very similar to a vulva. Today it is called Cunnu ’e s’Ebba, ‘vulva of the mare.’ But the reference runs to the vulva of the Mother Goddess, protector of waters and perennial excitant of the “sacred sperm” that God the Father emits by gathering the clouds and unleashing the fertilizing rain. The sacred orgasm converged into the sacred wells (that is, into the “sacred vagina” that received the heavenly water), where it was worshiped; but it could also be worshiped in particularly unique natural places, in natural sanctuaries like high-Gorropu, where a triangular convergence of tectonic lines gathers the waters on the grassy pebbles, which absorb them concealing the grand flowing Trinitarian to immediately reemit it in a pure unitary spring. That regular triangle of gorges and waters undoubtedly recalls the three lines of the female pubis through which the fertilizing seed penetrates to then emerge from the maternal womb as a unitary epiphany of life.”

Incidentally, Presèthu Tortu, as specified by Dedola himself, means “crooked, slanted basin. Presèthu, prethu is in the central dialect the basin, the rocky siphon where rainwater collects.”

The “Mereu” (note from the writer) is also called “Intro ‘e padente,” meaning nuraghe immersed in the forest.

The photos of the nuraghe Presethu Tortu are by Giovanni Sotgiu, Maurizio Cossu, and Cinzia Olias. What remains of one of the homonymous tombs of giants is captured by Alessandro Pilia. The photos of the nuraghe Intro ‘e Padente are by Giovanni Sotgiu and Maurizio Cossu. That of the waterfall “Cunnu ‘e s’Ebba” is by Billia Me_2013 for JuzaPhoto.