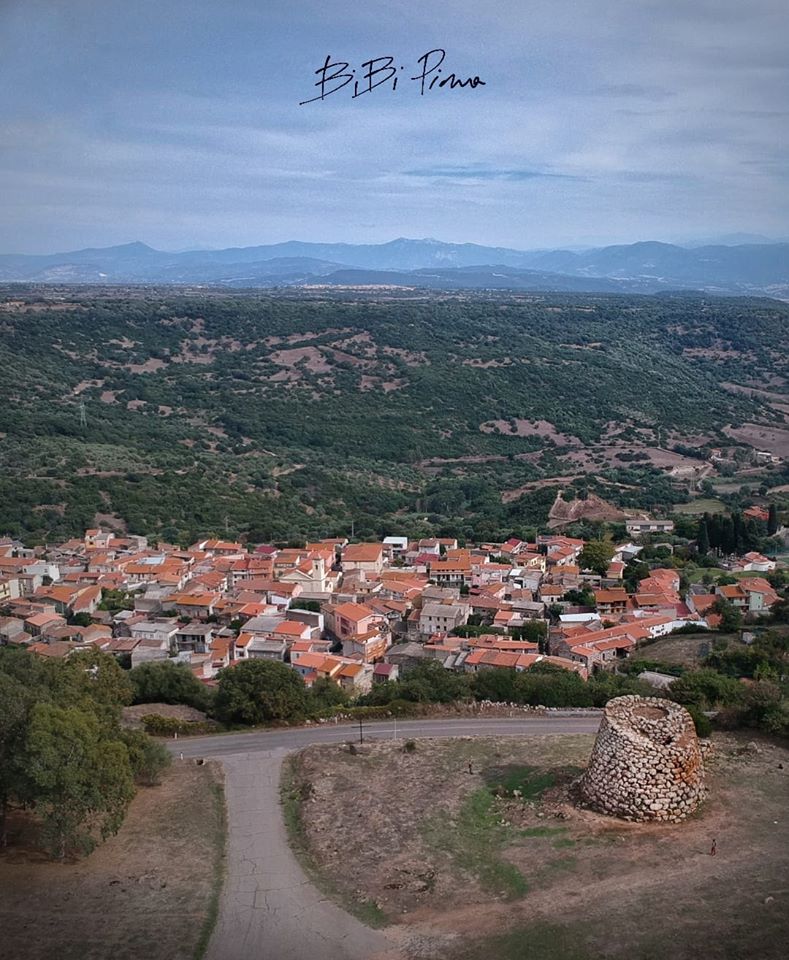

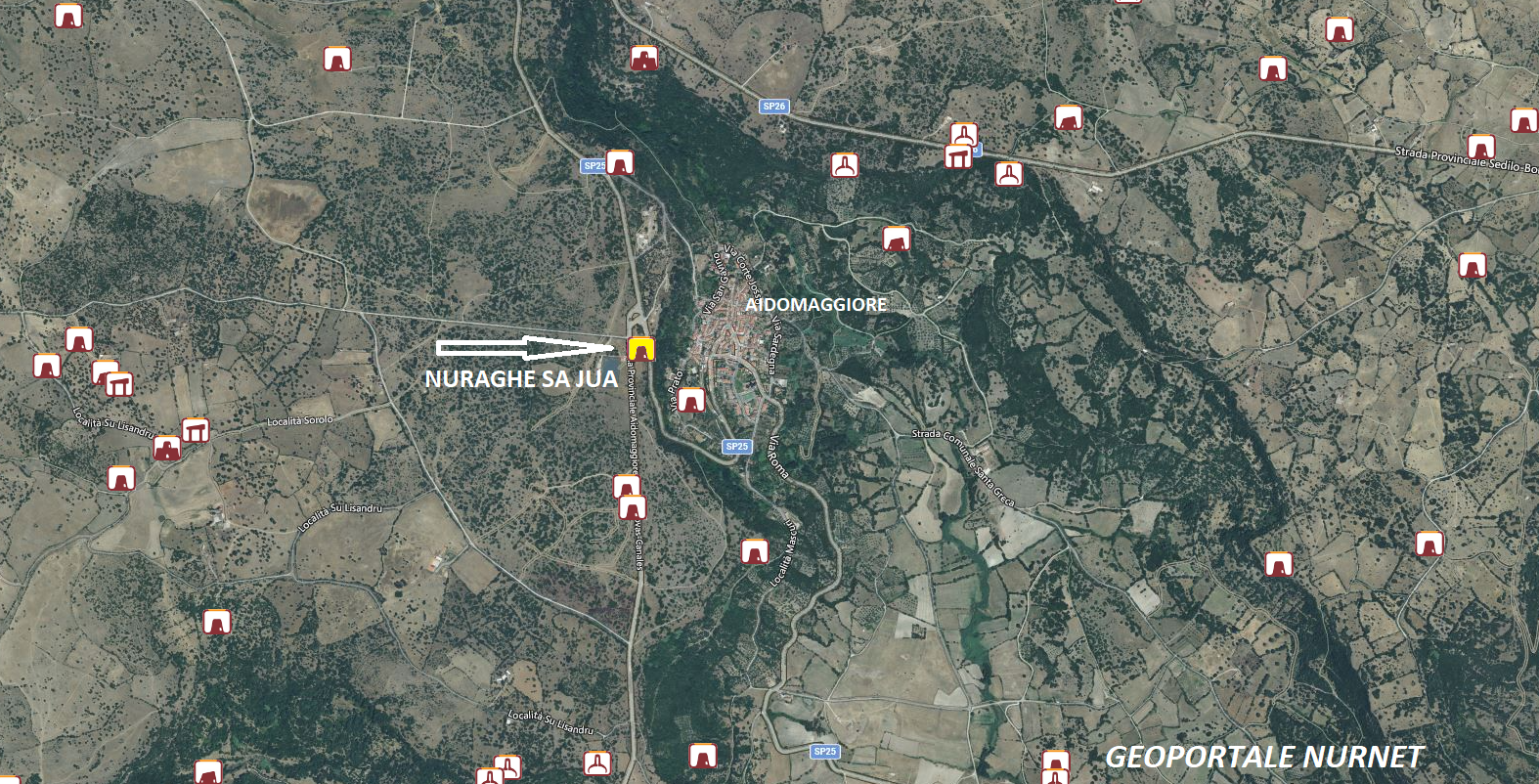

The nuraghe “Sa Jua” in Aidomaggiore evokes some singular considerations. In the Sardinian language, “Sa jua” is the part of the neck of animals on which “su ju” or “su juale” or “su juvale” rests, that is, the yoke. This device also indicates the very pair of cattle to which it is applied. The one composed of two Sardinian Modicana breed oxen traditionally carries the chariot of Sant’Efisio during the homonymous festival. The elders will probably remember “tziu Antoni,” who raised a double pair of oxen (one as a reserve for the other), assigned to transport the saint. The older “Su Ju” was made up of the pair “Bollemu” and “Po Tui” (I wish to live to see you always): names that highlighted the affection that bound the two animals. The two younger ones were called “Mancai Provisi” and “Non ci Arrenescisi” to poke fun at the fact that they would hardly measure up to the older pair. Aside from these amusing curiosities, “Su Ju,” in ancient Sardinian tradition, had another use. In this regard, Dolores Turchi writes that to facilitate the passing to a better life of suffering and dying people, “the greatest remedy was considered by all, as Angius states, the yoke of a plow or a cart. This tool was supposed to have a particular significance. During some of my research conducted several years ago in numerous villages, I found that almost all people of a certain age were aware of this practice. They also specified that the yoke had to be treated with ‘religious’ respect and that it should never be burned. According to some, prolonged agony was precisely due to the fact that the dying person had stained their life with the crime of burning a yoke.” The photos of the nuraghe Sa Jua are by Gianni Sirigu, Nicola Castangia, Bibi Pinna, Marco Cocco, and Sergio Melis.