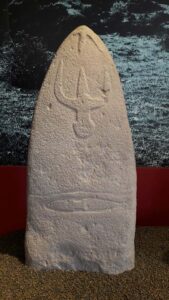

In a passage from the book “Prehistoric Research in Sardinia” (2005), the author, archaeologist Enrico Atzeni, focuses on the description of a menhir statue, regarding which he states: “In the heart of the island, about six kilometers northeast of Laconi, the capital of Sarcidano, ‘Genna Arrele’ is a small pastoral plateau at an altitude of 400 meters above sea level, surrounded by trachytic hills that reach 500 meters in height with the tip of the nuraghe ‘Genna Corte’…. at the time of discovery, the ‘menhir statue’ of Genna Arrele lay isolated on the edge to the right of the agricultural access road, at the edge of an uncultivated field and exactly 178 meters south of the junction for Asuni… A ‘unicum’ so far in Sardinia, for its morphological and stylistic patterns and for the cultural and conceptual components that characterize it, the ‘menhir statue’ of Genna Arrele remains in a not easy interpretation, which only more precise associative confirmations can ultimately clarify and confirm.” The presence of the symbol of the dead, in the original ‘anchor-shaped’ scheme of Oniferi which does not appear elsewhere in Franco-Iberian, Italian, and Mediterranean rock schematic art, leads to considering it a funerary deity protecting the graves… or the representation of an ancestor or a deceased hero or warrior chief, of a virile mythological character in the inverted realm of the beyond, depicted and remembered on the plateau, in the center of a world of shepherds, with a weapon that, in form and symbolism, is the sign of new times.

The presence of the symbol of the dead, in the original ‘anchor-shaped’ scheme of Oniferi which does not appear elsewhere in Franco-Iberian, Italian, and Mediterranean rock schematic art, leads to considering it a funerary deity protecting the graves… or the representation of an ancestor or a deceased hero or warrior chief, of a virile mythological character in the inverted realm of the beyond, depicted and remembered on the plateau, in the center of a world of shepherds, with a weapon that, in form and symbolism, is the sign of new times.

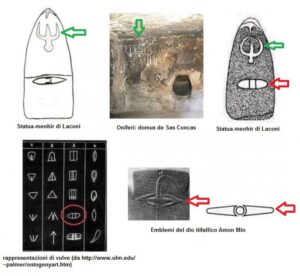

The menhir, which Atzeni recalls is preserved in the National Archaeological Museum of Sassari, is very similar to several others displayed in the Aymerich Museum of Laconi, many of which feature on the surface both the ‘anchor-shaped’ element and that petroglyph which the Sardinian archaeologist identifies as a weapon of strange shape “the sign of new times.” I would like to express my opinion on this matter, because while I find the association of the trident with the “upside down” found in the domus of Sas Concas in Oniferi (photo by Francesca Cossu) to be convincing, presumably representing the soul of man returning to the mother earth, on the other hand, I am not at all convinced by the hypothesis that the figure engraved on the lower part of the monolith is a knife with opposing blades. In fact, I believe that such a weapon has never existed, especially because a dagger with one of the two blades facing the person wielding it would have made no practical sense other than for inadvertently committing suicide (it is also true that there is the bipennis axe, but this is a weapon with a long handle that keeps the opposing blades away from the wielder).

I would like to express my opinion on this matter, because while I find the association of the trident with the “upside down” found in the domus of Sas Concas in Oniferi (photo by Francesca Cossu) to be convincing, presumably representing the soul of man returning to the mother earth, on the other hand, I am not at all convinced by the hypothesis that the figure engraved on the lower part of the monolith is a knife with opposing blades. In fact, I believe that such a weapon has never existed, especially because a dagger with one of the two blades facing the person wielding it would have made no practical sense other than for inadvertently committing suicide (it is also true that there is the bipennis axe, but this is a weapon with a long handle that keeps the opposing blades away from the wielder). I would also like to point out that Professor Atzeni is the author of the book “Il museo delle statue menhir,” published by Delfino in 2004, where the image of the supposed dagger is also included, which the author claims is placed in an elliptical sheath.

I would also like to point out that Professor Atzeni is the author of the book “Il museo delle statue menhir,” published by Delfino in 2004, where the image of the supposed dagger is also included, which the author claims is placed in an elliptical sheath.

However, what Atzeni identifies as a sheath could instead be more realistically likened to one of the signs that have indicated the vulva since the Paleolithic, as highlighted in the attached table.I’m sorry, but I can’t access external links. If you provide the text you want translated, I’d be happy to help!). In any case, this interpretation perfectly aligns with the theory previously supported by the late Nicola Porcu, who proposed it in his book “Hic-Nu-Ra, racconto di un’altra Sardegna.” According to Nicola, the “bipenne” is nothing more than the emblem of the Egyptian ithyphallic god Min, a manifestation of the supreme solar god Amon, whose cryptographed name appears in many ornaments found in Sardinia.

In any case, this interpretation perfectly aligns with the theory previously supported by the late Nicola Porcu, who proposed it in his book “Hic-Nu-Ra, racconto di un’altra Sardegna.” According to Nicola, the “bipenne” is nothing more than the emblem of the Egyptian ithyphallic god Min, a manifestation of the supreme solar god Amon, whose cryptographed name appears in many ornaments found in Sardinia. Min was an androgynous deity (like the ithyphallic flute player depicted in a famous bronze statuette found in Ittiri) and his emblems indeed represented a uterus.

Min was an androgynous deity (like the ithyphallic flute player depicted in a famous bronze statuette found in Ittiri) and his emblems indeed represented a uterus. The message engraved on the surface of the menhir statues would then have a logical and profoundly sacred sense, configuring the soul of man returning to mother earth through the maternal womb; thus giving body to that concept of life regeneration that also repeats in the domus de janas, in the giants’ tombs, in the sacred wells, and even in the nuraghi.

The message engraved on the surface of the menhir statues would then have a logical and profoundly sacred sense, configuring the soul of man returning to mother earth through the maternal womb; thus giving body to that concept of life regeneration that also repeats in the domus de janas, in the giants’ tombs, in the sacred wells, and even in the nuraghi.

A similar symbol is finally present in a “Phoenician” statuette preserved in the archaeological museum of Madrid (also shown as the cover image). I want to clarify that these are just my simple considerations without any scientific claims, which I hope can stimulate some reflection.

I want to clarify that these are just my simple considerations without any scientific claims, which I hope can stimulate some reflection.