In the middle of the 12th century BC, during a period contemporary to the fall of Troy, the Nuragic civilization reached its peak in Sardinia. The proto-nuraghi or corridor nuraghi dating back to the “early bronze” period (approximately 1800/1650 BC) had been supplanted by “monotower” structures and then by complex nuraghi surrounded by powerful bastions that included internal courtyards and a number of towers ranging from two to more towers. Inside the perimeter wall of the central “tholos,” whose height sometimes reached 25/30 meters, there was generally a stone staircase leading to the upper floor or floors. Today, there are over eight thousand of these monuments, expressions of a unique civilization on a planetary level and constructed with enormous stone blocks, although it is estimated that their original number was much higher, and they represent the most extensive and dense archaeological heritage in the world.

It is intuitive to imagine the visual impact on those arriving on our island, perhaps coming from other Mediterranean regions where the prevailing building size was comparable to that of a hut, when faced with these giants of stone that must have appeared as proto-skyscrapers towering from the heights and rocky cliffs near the coast or emerging from the dense vegetation that once characterized the Sardinian landscape.

Of these extraordinary monuments, a powerful identity icon of our island, there is discussion in one of the volumes of the “Sardegna Archeologica” series (guide no. 57 edited by Emerenziana Usai and Raimondo Zucca – Carlo Delfino publisher, 2015), from which the following excerpts are taken:

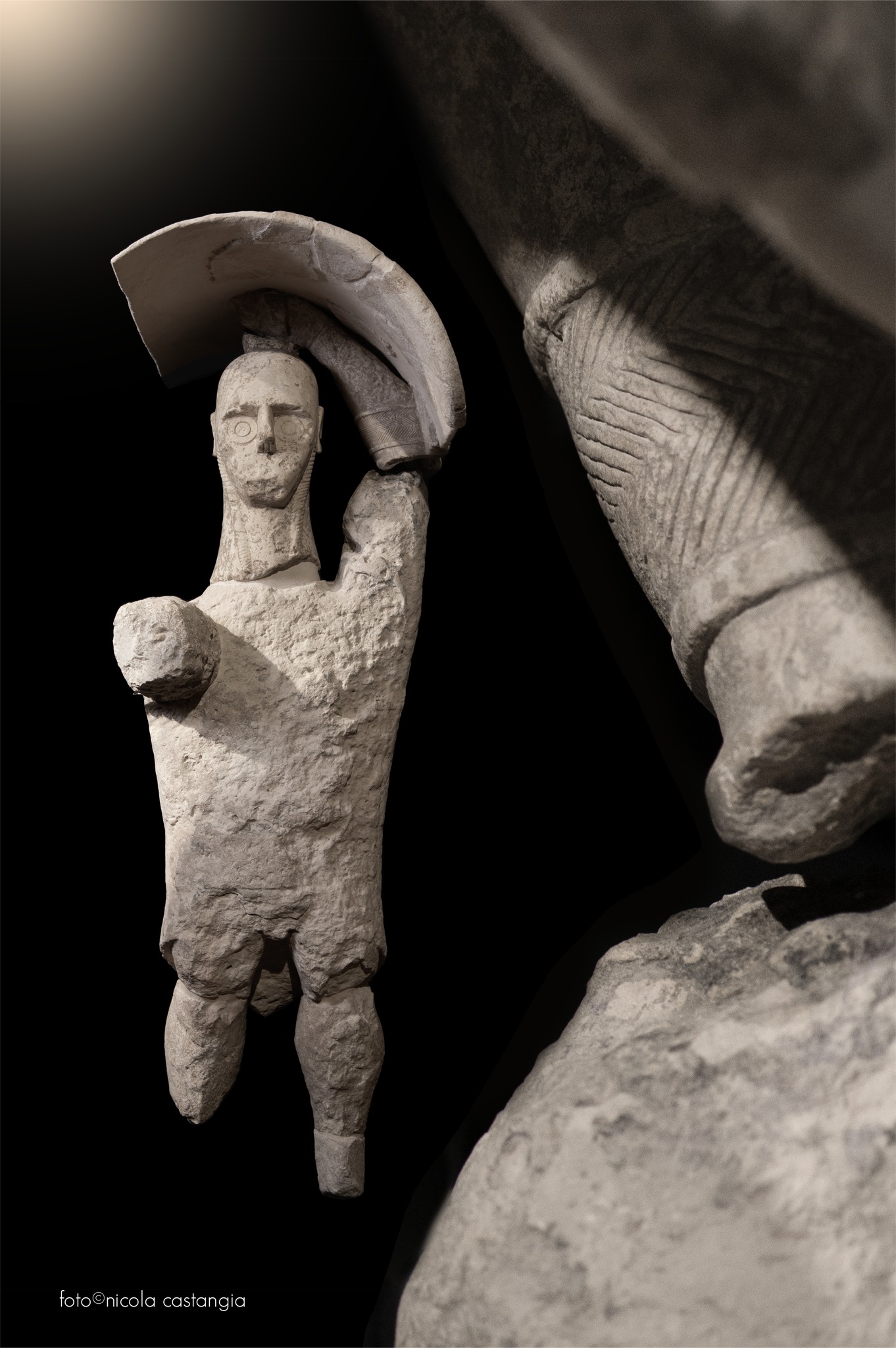

“Giovanni Lilliu defined the ‘beautiful age of the nuraghi,’ the most significant and productive period of the Nuragic civilization, attributable to the Recent and Final Bronze Age (14th-10th century), its phase III which is now assigned to the chronological span between the Middle, Recent Bronze and the beginnings of the Final Bronze Age (15th-12th century), in which this extraordinary building experience of the Sardinians unfolded, lasting three or four hundred years, structuring the entire regional territory through the construction of about 7000 nuraghi and 800 giant tombs. The ‘people of the nuraghi’ developed forms of control over the Sardinian territory, according to models partly already experimented during the Copper Age and in the Early Bronze Age, but was innovative in the development of a standard architecture – the nuraghe – which, moving through experiments and failed attempts, as is the case with unfinished nuraghi, managed to elaborate, in not always evolutionary forms, the corridor nuraghi and the ‘tholos’ nuraghi of the single tower type and multiple towers in both the ‘tancato’ form with two towers connected by curtains to the original tower, and in the forms of the ‘polilobati’ nuraghi with a central tower rising within a triangular bastion with three towers, quadrangular with four towers, polygonal with five or more towers. The nuraghi could also be enclosed by a turrited ‘antemurale’ with six, seven, eight or more towers, constituting hierarchical forms. The nuraghi marked the territory of a community, in relation to a ‘colonization’ or anthropization of cleared or improved areas for crops, pastures, and other economic activities. They strongly characterized the territory in which they were integrated, serving as points of control, visual communication systems, demarcation, habitation, and fortress. They were and are the most characteristic element of the Nuragic civilization, a significant mark that becomes a symbol. The villages of the ‘beautiful age of the nuraghi’ are not well known, although forms of settlement in circular or elliptical huts, with a stone base and raised in raw bricks or equally in stone, with thatch roofs are documented.” (ellipsis) “The ‘beautiful age of the nuraghi’ evolves at the beginning of the 1st millennium BC into a protosard culture that, enriched by interaction with Mediterranean cultures it relates to, looks back at the architectural past of the nuraghi and the giant tombs, preserving signs of the transition, sometimes reusing both, at other times abandoning them. Villages arise in the shadow of the nuraghe or in areas of new settlement lacking nuraghi. The catalyst element is now the sanctuary (the well temple, the ‘megaron’ temple, the ‘rotunda’), whose construction dates back already in several cases to the end of the 2nd millennium BC. The ‘buildings constructed (in Sardinia) in the archaic manner of the Greeks,’ according to the phrase from the text attributed to Aristotle ‘On Wonderful Things,’ are the nuraghi and other Nuragic architectures of the Bronze Age, which did not have a bard like Homer who narrated in verse the epic of the Achaean heroes in the Trojan War or along the perilous routes home to their mainland or island kingdoms. But the story of the ‘beautiful age of the nuraghi’ is perhaps recognizable in Sinis, in the place of Mont’e Prama, where in 1974, at the dawn of the birth of the province of Oristano, fragments of nuraghe models and limestone statues began to be discovered that tell stories whose decipherment has engaged archaeologists for four decades.”

Attached: The protonuraghe Bruncu Madugui in Gesturi (ph. Marco Cocco); the single tower nuraghe Crabia in Bauladu (ph. Gianni Sirigu); the tancato nuraghe Sa Domu ‘e s’Orku in Sarrock (ph. Nuraviganne); the polilobati nuraghi Nuraddeo in Suni, Arrubiu in Orroli and S’Uraki in San Vero Milis, respectively in photos by Andrea Mura-Nuragando Sardegna, Diversamente Sardi and Bibi Pinna; the Nuragic village of Serra Orrios in Dorgali (ph. Andrea Mura–Nuragando Sardegna); the well temple of Irru in Nulvi (ph. ArcheoUri Vagando); the megaron temple Sa Domu ‘e Orgia in Esterzili (ph. Bibi Pinna); the ceremonial rotunda of Sa Sedda ‘e sos Carros in Oliena (ph. Lucia Corda); a model of a nuraghe and a statue from Monte ‘e Prama in Cabras (ph. Nicola Castangia).