In the essay by Dolores Turchi “L’incubazione nella civiltà nuragica”, the following is written:

<<The philosopher Filippo, in the 6th century AD, wrote: “Some writers have passed down that certain people afflicted by ailments would go far away, to (the tombs) of the heroes in Sardegna and would heal; thus, they would lie down to sleep for a duration of five days, after which, upon waking, they believed that the moment (in which they awoke) was the same as when they had laid down next to the heroes.” While Semplicio, a contemporary of Philoponus, commenting on the same passage of Aristotle, adds an important detail: “Up until the time of Aristotle, it was said that of the nine boys born to Heracles by the daughters of Thespius, the bodies remained incorrupt and intact and appeared to be in a state of sleep.”

While Semplicio, a contemporary of Philoponus, commenting on the same passage of Aristotle, adds an important detail: “Up until the time of Aristotle, it was said that of the nine boys born to Heracles by the daughters of Thespius, the bodies remained incorrupt and intact and appeared to be in a state of sleep.” “These are therefore the heroes (venerated) in Sardinia.” From this passage, it is clear that the bodies were embalmed; but in order for these heroes to remain intact and uncorrupted, they not only had to be located within temples, a fact already provided to us by Tertullian, but also be kept under guard. Various scholars have hypothesized that these heroes were placed in the tombs of giants and that the incubation occurred in the exedra of these.

“These are therefore the heroes (venerated) in Sardinia.” From this passage, it is clear that the bodies were embalmed; but in order for these heroes to remain intact and uncorrupted, they not only had to be located within temples, a fact already provided to us by Tertullian, but also be kept under guard. Various scholars have hypothesized that these heroes were placed in the tombs of giants and that the incubation occurred in the exedra of these. The hypothesis of the embalming of corpses and their subsequent deposition inside the tombs of giants, supported by Turchi, is not a trivial consideration, even if I have no evidence of objective verifications. Or rather, to my knowledge, there is only one reference summarized in an article that appeared on the pages of Unione Sarda on January 18, 2007, where the archaeologist Piero Bartoloni, regarding the findings in the necropolis of Sulky in S.Antioco, wrote: “How to explain the bandages that wrapped the head of one of the deceased, almost as if it were a mummy? Never seen before. Perhaps it was a widespread custom even though no trace had ever been found, in those rites and ‘Egyptianizing’ superstitions that were very common among Phoenicians and Punics.”

The hypothesis of the embalming of corpses and their subsequent deposition inside the tombs of giants, supported by Turchi, is not a trivial consideration, even if I have no evidence of objective verifications. Or rather, to my knowledge, there is only one reference summarized in an article that appeared on the pages of Unione Sarda on January 18, 2007, where the archaeologist Piero Bartoloni, regarding the findings in the necropolis of Sulky in S.Antioco, wrote: “How to explain the bandages that wrapped the head of one of the deceased, almost as if it were a mummy? Never seen before. Perhaps it was a widespread custom even though no trace had ever been found, in those rites and ‘Egyptianizing’ superstitions that were very common among Phoenicians and Punics.”

It would therefore be a matter of discovering whether, as Turchi claims, the ritual of embalming was already in vogue during the Nuragic period when the tombs of giants were built and whether it continued into the Punic-Phoenician period, as the finding of the “mummy” of Sulky seems to demonstrate. The hypothesis that the “uncorrupted corpses” of Semplicio were just a product of his imagination is also legitimate.

Fortunately, “denialism” by preconceived notions does not belong to our DNA, while it stimulates our curiosity to understand what the customs of our ancestors were, but also to comprehend who they were and where they came from.

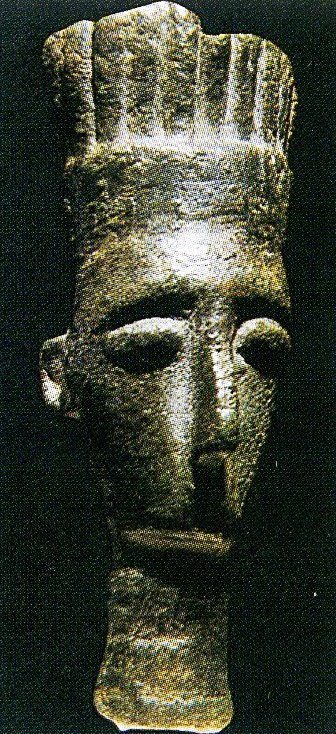

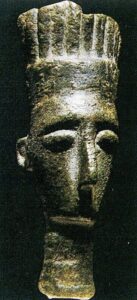

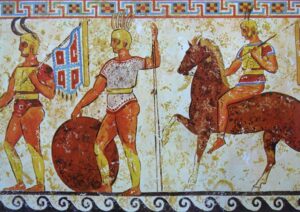

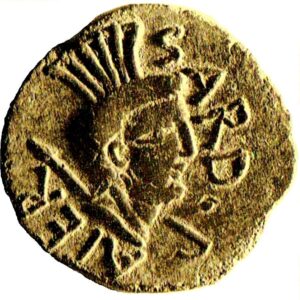

A clue is offered to us by the great archaeologist Giovanni Garbini, who, on the occasion of the discovery of an amphora with Philistine inscriptions at the site of S’Arcu ‘e is Forros in Villagrande Strisaili, stated (“Archeologia Viva” Sept./Oct. 2011) that the archaeological context to which the amphora and the related inscription (XII-VII century B.C.) belong allows us to outline “a rather unexpected historical-cultural picture of Sardinia, with a widespread Levantine presence across the island since the 13th century B.C. and particularly interested in the search and processing of metals. The Phoenician colonists who settled on the southwestern coast had been preceded by other Phoenicians who had allied with the Philistines and who, like them, lived in the nuraghi alongside the local population…”. As much as there are various doubts about the Phoenician presence in Sardinia from such an early time (Dimitri Baramki, curator of the Beirut museum, claimed that the Phoenicians learned the technique of deep-sea navigation only in the 11th century BC, after merging with the Sea Peoples who had invaded their territory around 1200 BC), different considerations are warranted regarding the Philistines: those Pheleseth with feathered headdresses who appear consistently alongside the Shardana at least since the time of Pharaoh Ramses II (19th dynasty – 1279/1212 BC).

As much as there are various doubts about the Phoenician presence in Sardinia from such an early time (Dimitri Baramki, curator of the Beirut museum, claimed that the Phoenicians learned the technique of deep-sea navigation only in the 11th century BC, after merging with the Sea Peoples who had invaded their territory around 1200 BC), different considerations are warranted regarding the Philistines: those Pheleseth with feathered headdresses who appear consistently alongside the Shardana at least since the time of Pharaoh Ramses II (19th dynasty – 1279/1212 BC).

It seems established that the Philistines came from the biblical Kaftor/Keftiou, an island that according to Giovanni Garbini would be identified with Crete. However, it is likely that in ancient times the name of present-day Crete was instead “Minous.”

Berni and Chiappelli, in their book “Haou-Nebout, the Sea Peoples,” provide interesting references from the writings of the famous French Egyptologist Jean Vercoutter (1911-2000), including a passage from the “Poetic Stele” of Thutmose III in which it is written “I made it so that you tread upon the lands of the West, Keftiou and Isy…;” and another taken from a text accompanying the depictions found in the tomb of the noble Amenemheb (17th dynasty – 1550/1291 BC), where “the kings of the land Keftiou and Menous” are mentioned.

Passages that indeed suggest that Kaftor/Keftiou was located to the west among the islands of the “Great Green” and that Menous/Minous/Crete was instead one of its colonies in the eastern Mediterranean. This hypothesis would in turn justify the western origins of the Minoans from Crete, as evidenced by relatively recent genetic studies, but could also provide support for the doubts about the homeland of the Pheleset/Philistines. If it is assumed that the Philistines could have come from a western land (and not, as Garbini argues, from the island of Crete where no trace of this ethnicity has ever been found), their likely proximity to Sardinia would explain the solid and lasting alliance with the Shardana.

If it is assumed that the Philistines could have come from a western land (and not, as Garbini argues, from the island of Crete where no trace of this ethnicity has ever been found), their likely proximity to Sardinia would explain the solid and lasting alliance with the Shardana. It cannot be excluded, however, that the Shardana and Philistines were both settled on our island, where Philistine traces have been found at S.Maria di Nabui (Gulf of Oristano), Macomer (the ancient Macompsisa), Serra Orrios (Dorgali), and at S’Arcu ‘e is Forros (Villagrande Strisaili).

It cannot be excluded, however, that the Shardana and Philistines were both settled on our island, where Philistine traces have been found at S.Maria di Nabui (Gulf of Oristano), Macomer (the ancient Macompsisa), Serra Orrios (Dorgali), and at S’Arcu ‘e is Forros (Villagrande Strisaili).

However, there are other passages, also taken from the writings of Vercoutter, in which the Egyptologist states that Keftiou was “a country rich in precious materials, because it had mines, which served as an intermediary between the mining regions and Egypt, and also that it had numerous and skilled metallurgical artisans,” noting among other things that Keftiou’s trade involved “both finished products and raw materials.” In this regard, it is relevant to observe that Sardinia has historically been the “land of metals,” a primary producer of silver (argyrophleps nesos), copper, and other metals, and that the Sardinians and Philistines were notoriously skilled metallurgical craftsmen.

In this regard, it is relevant to observe that Sardinia has historically been the “land of metals,” a primary producer of silver (argyrophleps nesos), copper, and other metals, and that the Sardinians and Philistines were notoriously skilled metallurgical craftsmen.

Vercoutter also writes that “products made in Keftiou are found in northern Syria as well as in Mari. Moreover, the presence of gold and especially silver in ingots leads one to consider the country of Keftiou as an intermediary between one or more countries producing these metals and Egypt.”

Vercoutter reports, among various mineral products, also lapis lazuli, but their presence can be justified by the mediating role assigned to Keftiou by the same French Egyptologist, who finally states that Egypt would either import or go to fetch a certain stone from the country of Keftiou,” which he identifies with amber, coming precisely from Keftiou where it was called “memno.”

However, regarding this stone, another great Egyptologist, the Englishman Sir Alain Gardiner (1879-1963), wrote: “it may be that the so-called amber was not a worked resin, but the beautiful mineral of a brilliant black known as obsidian” (“The Egyptian Civilization”).

Regarding this latter assertion, I believe it is interesting to observe that the stone mentioned by Vercoutter and which Gardiner assumes was obsidian could reasonably have come from the quarries of Mount Arci, considering that this mineral was exported by the Sardinians, by sea, at least since the 6th millennium BC.

But it seems there was another custom typical of the Pheleseth of Keftiou: that of embalming, which was mentioned at the beginning of this post. In this regard, Berni and Chiappelli refer to an Egyptian text written between 2200 and 2000 BC, in which it is stated: “Of course, one no longer goes down to Byblos today, what shall we do for the pines destined for our mummies, thanks to whose importation the priests are buried, and with the oil of which [the kings] are embalmed as far away as the country of Keftiou,” and they also cite the Egyptologist Vercoutter when he observes.that“The term Keftiou has been clearly used here to designate, in the mind of the writer, the farthest point reached by Egyptian influence. Therefore, it must be admitted that the Egyptian scribes, from the 8th to the 10th dynasty, were aware of the existence of the country Keftiou. They considered it very distant, but still under Egyptian influence since the kings of this country claimed to be embalmed, and embalming is a purely Egyptian technique. […]. Finally, we note that the scribe mentions only the embalming of priests and kings, which dates back to a time when the technique of mummification was still little widespread in Egypt and confirms the ancient date of the archetype manuscript.” (“Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale”). All this being said, at the risk of appearing once again as “enthusiastic sardocentrics” and considering that we are expressing simple hypotheses, it is reasonable to quietly ask whether, by mentioning Keftiou as the homeland of the Pheleseth, the ancient Egyptians were indeed referring to Sardegna, with which, apart from commercial exchanges, they perhaps shared specific rituals such as embalming.

All this being said, at the risk of appearing once again as “enthusiastic sardocentrics” and considering that we are expressing simple hypotheses, it is reasonable to quietly ask whether, by mentioning Keftiou as the homeland of the Pheleseth, the ancient Egyptians were indeed referring to Sardegna, with which, apart from commercial exchanges, they perhaps shared specific rituals such as embalming.

The photos of the giant tombs Sa Domu ‘e s’Orku (Siddi) and San Cosimo (Gonnosfanadiga) are respectively by Diversamente Sardi and Lucia Corda, while the photos of the nuragic villages of S’Arcu ‘e is Forros (Villagrande Strisaili) and Serra Orrios (Dorgali) are by Nuragando.