The religiosity of the nuragic Sardinians was characterized, in particular, by the worship of waters, which represented in some ways a “blessing” of nature, but sometimes also the means through which divine judgment manifested itself. Raffaele Pettazzoni, the foremost Italian historian of religions (“La religione primitiva in Sardegna”- 1912), recounts that “in certain places” in Sardegna “there are numerous hot springs, miraculous for their therapeutic effects, particularly effective for the treatment of eyes. On the eyes, they also have another effect: those suspected of theft are subjected to the water test, that is, a washing of the eyes; if innocent, their sight sharpens; if guilty, they become blind. This Sardinian rite, where the same magical element that operates therapeutically is also used for a kind of “judgment of God,” faithfully reflects the characteristics of primitive religious thought, which does not yet clearly distinguish between the physical world and the moral world.” The worship of waters is a theme that will be addressed later by other authors, including particularly Giovanni Lilliu, who in the book “Sardegna Nuragica” (2006), wrote: “Temples and springs are significant testimonies of a religion that is underpinned by the scarcity of waters. Architectures that evoke both the art that the nuragic civilization was capable of to collect and preserve, like in a treasure chest, the precious liquid element for fields, livestock, and humans themselves. And the drought (“sa siccagna” as the Sardinians call it today): an ancient evil like plague, famine, and hunger. Which, or what, deities or supreme beings did the nuragic people invoke to counter this “infernal cycle!? Certainly the “infernal” underground spirit, which they believed resided in wells and springs, namely the bull. The bull heads carved on the facades of the temples of Sàrdara and Serri are, more than clues, proof. Additionally, bronze and terracotta materials were found confirming this, depicting or bearing signs of the divine animal. In the deposits of the sacred well of Camposanto-Olmedo, there was a bronze idol in the form of a bull protome; votive vessels from the well of Serri have surfaces marked by stylized bovine horns; From the well of Sàrdara comes the remains of a pear-shaped amphora, where a strange anthropomorphic being holds a horned staff to its chest (here too, among the ritual vessels, there is one with a neck shaped like a “phallus,” a symbol that befits the fertilizing bull just like water). Additionally, the God-Bull is salutary. This is indicated by the names of “Sa funtana de sos malàvidos” in Orani and “sa funtana de is dolus” in Sardara, and it is reaffirmed by ancient authors when they recall the physical and psychic healing virtues of the spring waters.

From the well of Sàrdara comes the remains of a pear-shaped amphora, where a strange anthropomorphic being holds a horned staff to its chest (here too, among the ritual vessels, there is one with a neck shaped like a “phallus,” a symbol that befits the fertilizing bull just like water). Additionally, the God-Bull is salutary. This is indicated by the names of “Sa funtana de sos malàvidos” in Orani and “sa funtana de is dolus” in Sardara, and it is reaffirmed by ancient authors when they recall the physical and psychic healing virtues of the spring waters. It is possible that the same “infernal” being entered into judging the wicked. In those distant times, positive law did not exist. Revealing guilt or innocence was believed to belong to the supra-sensible, which manifested through mysterious natural phenomena. The effect of these was the basis for the punishment or absolution of the crime. Ancient sources tell that in Sardegna, the judgment of God was entrusted to the hot waters (the same that cured and healed the diseases of men), that is, to the god of waters. It is the ordalia of water, of which there exists a very interesting archaeological document. Near the rural church of Santa Lucia (note, the saint “of the eyes”, of light) in Bonorva, numerous thermal mineral springs, effervescent, spring from the trachytic soil. Once, a dense collection of such springs was gathered inside a circular enclosure, measuring 35 x 36 meters in diameter, shaped like a cavea as an amphitheater, where the crowd sat as a collective witness of the ordalical ceremony. The suspect of theft (the abigeato, an ancient inglorious virtue of the Sardinian shepherd) was subjected to the judgment of God. After the “stopped” person’s oath, those in charge of the ritual would immerse his head in the hot, sparkling water.

It is possible that the same “infernal” being entered into judging the wicked. In those distant times, positive law did not exist. Revealing guilt or innocence was believed to belong to the supra-sensible, which manifested through mysterious natural phenomena. The effect of these was the basis for the punishment or absolution of the crime. Ancient sources tell that in Sardegna, the judgment of God was entrusted to the hot waters (the same that cured and healed the diseases of men), that is, to the god of waters. It is the ordalia of water, of which there exists a very interesting archaeological document. Near the rural church of Santa Lucia (note, the saint “of the eyes”, of light) in Bonorva, numerous thermal mineral springs, effervescent, spring from the trachytic soil. Once, a dense collection of such springs was gathered inside a circular enclosure, measuring 35 x 36 meters in diameter, shaped like a cavea as an amphitheater, where the crowd sat as a collective witness of the ordalical ceremony. The suspect of theft (the abigeato, an ancient inglorious virtue of the Sardinian shepherd) was subjected to the judgment of God. After the “stopped” person’s oath, those in charge of the ritual would immerse his head in the hot, sparkling water. Ancient authors conclude by saying that if the accused could not withstand the terrible effect, he became blind for having perjured himself, and thus his guilt was established; if, on the other hand, he overcame it and even saw more clearly, it meant that he had not sworn falsely and was innocent.

Ancient authors conclude by saying that if the accused could not withstand the terrible effect, he became blind for having perjured himself, and thus his guilt was established; if, on the other hand, he overcame it and even saw more clearly, it meant that he had not sworn falsely and was innocent.

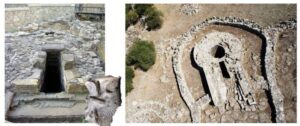

In the images: the sacred wells of Sant’Anastasìa (“sa funtana ‘e is dolus”), in Sardara, and that of S.Vittoria in Serri in the photos by Francesca Cossu. Also attached is “sa funtana is dolus” with the shard overlay in which the “being with horned stick” mentioned by Giovanni Lilliu appears.