In her description of the nuraghe Su Mulinu di Villanovafranca (I Tesori dell’Archeologia edited by Alberto Moravetti), archaeologist Lavinia Foddai particularly states that this monument “located on the hill that dominates the course of the rio Mannu… was excavated for the first time in the 1960s by Giovanni Lilliu and subsequently by Giovanni Ugas… The site, resulting from three distinct construction phases, includes a complex nuraghe equipped with a protective wall and a vast village. The oldest phase (Middle Bronze I, 16th-15th century B.C.) dates back to a building, of yet undefined layout, surrounded by a radial wall characterized by corridors and cells with ogival closures. In a second phase (Middle Bronze II, 14th century B.C.) a trilobate bastion with a concave-convex profile (m.21×22) is added to the older building, which on the lower floor features several elliptical cells and short corridors with a truncated-ogival section, while the arrangement of the rooms on the upper floor remains difficult to interpret. A new outer wall is added to the bastion, consisting of straight curtains that encompass four circular towers, while a vast settlement that has been renovated several times over the years develops in the surrounding area. The third phase (Late Bronze Age, 12th century B.C.) is characterized by some significant changes: the construction of a new bastion and an additional circular tower, the so-called tower E, and the renovation of the outer wall with the building of a new tower equipped with loopholes (tower F) and straight curtains.

A new outer wall is added to the bastion, consisting of straight curtains that encompass four circular towers, while a vast settlement that has been renovated several times over the years develops in the surrounding area. The third phase (Late Bronze Age, 12th century B.C.) is characterized by some significant changes: the construction of a new bastion and an additional circular tower, the so-called tower E, and the renovation of the outer wall with the building of a new tower equipped with loopholes (tower F) and straight curtains. The excavation of room E, located in the lower level of the bastion, allowed for the discovery of an exceptional altar made of sandstone (late IX-VIII century B.C.), a bench-seat, and two ritual hearths that testify to the transformation of the nuraghe into a place of worship. The altar, which replicates the layout and height of the bastion of the fortress, is composed of three stacked elements and is equipped with a channel and a basin where liquids poured into a basin made on the top flowed.

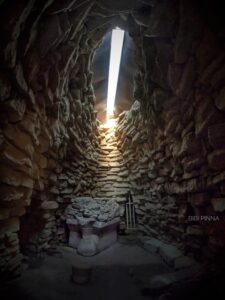

The excavation of room E, located in the lower level of the bastion, allowed for the discovery of an exceptional altar made of sandstone (late IX-VIII century B.C.), a bench-seat, and two ritual hearths that testify to the transformation of the nuraghe into a place of worship. The altar, which replicates the layout and height of the bastion of the fortress, is composed of three stacked elements and is equipped with a channel and a basin where liquids poured into a basin made on the top flowed. The surfaces of the altar were crowned with bronze objects, perhaps long rods, while below the reproduction of the terrace’s crown is carved in relief a motif of ‘crescent moon’. The altar basin is linked to the celebration, in the nuraghe, of sacred rites that involved a complex liturgy based on the sacrifice of animals and the offering of votive artifacts. The ceremonies, related to the sphere of agro-pastoral fertility, could accompany both the initiation of young people who surpassed puberty and those who became part of a socially elevated group. The arrival of the Carthaginians (end of the 6th century B.C.) causes a new abandonment of the site and the interruption of sacred rituals, which, however, resume and persist during the Roman era (second half of the 1st century B.C. – first half of the 1st century A.D.), when the upper element of the nuragic altar, equipped with a drain, is removed and replaced by a stone and mortar wall. I presume that Dr. Foddai, referring to the “transformation of the nuraghe into a place of worship” (end of the 9th-8th century B.C.), intended to suggest a previous and different use (perhaps as a fortress or at least that’s how I understood it). However, to this latter hypothesis, which is certainly legitimate, another equally reasonable one could be opposed, attributing to the complex of Su Mulinu a sacramental use “ab origine”.

The surfaces of the altar were crowned with bronze objects, perhaps long rods, while below the reproduction of the terrace’s crown is carved in relief a motif of ‘crescent moon’. The altar basin is linked to the celebration, in the nuraghe, of sacred rites that involved a complex liturgy based on the sacrifice of animals and the offering of votive artifacts. The ceremonies, related to the sphere of agro-pastoral fertility, could accompany both the initiation of young people who surpassed puberty and those who became part of a socially elevated group. The arrival of the Carthaginians (end of the 6th century B.C.) causes a new abandonment of the site and the interruption of sacred rituals, which, however, resume and persist during the Roman era (second half of the 1st century B.C. – first half of the 1st century A.D.), when the upper element of the nuragic altar, equipped with a drain, is removed and replaced by a stone and mortar wall. I presume that Dr. Foddai, referring to the “transformation of the nuraghe into a place of worship” (end of the 9th-8th century B.C.), intended to suggest a previous and different use (perhaps as a fortress or at least that’s how I understood it). However, to this latter hypothesis, which is certainly legitimate, another equally reasonable one could be opposed, attributing to the complex of Su Mulinu a sacramental use “ab origine”. The construction of the altar and the other annexes would therefore be configured as a sort of re-furnishing of the space where religious ceremonies took place, which would continue in the following centuries. The abundance of towers that characterizes the complex, as well described by Dr. Foddai, does not conflict with such use, because the ceremonial area certainly required other “accessory” spaces, similarly to what happened in religious architecture, particularly referring to Christian architecture, when the primitive and “essential” places of worship were gradually replaced by increasingly imposing and complex churches and basilicas.

The construction of the altar and the other annexes would therefore be configured as a sort of re-furnishing of the space where religious ceremonies took place, which would continue in the following centuries. The abundance of towers that characterizes the complex, as well described by Dr. Foddai, does not conflict with such use, because the ceremonial area certainly required other “accessory” spaces, similarly to what happened in religious architecture, particularly referring to Christian architecture, when the primitive and “essential” places of worship were gradually replaced by increasingly imposing and complex churches and basilicas.

The photos of the nuraghe Su Mulinu di Villanovafranca are by Antonello Gregorini and Bibi Pinna.