In 2006, an article by Alberto Moravetti was published in the “Quaderni di Darwin,” of which we propose the “incipit”:

“The discovery of Monte d’Accoddi dates back to the early fifties of the last century and occurred as part of a broader program of interventions promoted by the still young Autonomous Region of Sardinia, aimed both at resuming research activities interrupted due to wartime events and at fostering employment in those difficult post-war days that were dragging on in the island. The project included the opening of several important archaeological sites: two were planned in the southern part of the island and at least one in the north.

For the first, the choice fell on the nuragic complex of Barumini, now a UNESCO World Heritage site, and then on the Punic city of Nora, while for the third archaeological site, the intervention was desired by the “palazzo” and in particular by the then Minister of Public Education, a Sardinian who would later become President of the Republic.

Indeed, Professor Antonio Segni, a prominent legal scholar but also passionate about archaeology, had become convinced that a mysterious little hill that rose in land adjacent to his property, about ten kilometers from Sassari, was nothing more than an Etruscan mound or something similar, and for this reason, he had advocated for its excavation and funding.

However, to carry out this undertaking, an archaeologist was needed, which was not simple at that time since Sardinia could count on only one Superintendency of Antiquities, based in Cagliari, and two archaeological officials, for the protection of a vast territory.

It was therefore necessary to call back a young Sardinian archaeologist – Ercole Contu – from the Superintendency of Bologna, where he was serving, destined to become superintendent of Antiquities for the provinces of Sassari and Nuoro and now an emeritus professor of Sardinian Antiquities at the University of Sassari.

Contu recounts returning to the island reluctantly: he was indeed convinced that the so-called “mound” was nothing but the ruin of one of the many nuraghi, about seven thousand, that characterize the island’s landscape and that are numerous in the Nurra, the historical region where the hill of Monte d’Accoddi stood.

But the excavations revealed that everyone, archaeologists and non-archaeologists alike, had been mistaken.

Indeed, the investigations demonstrated that the hill not only did not hide any nuraghe but was produced from the ruins of an exceptional and so far unique prehistoric monument, much older than the first nuraghi. Unfortunately, due to its dominant position in a mostly flat territory, the height was chosen during the last war to set up anti-aircraft batteries at the corners, which severely damaged the upper layers of the monument.

The exploration of Monte d’Accoddi took place in two distinct periods, with an interval of about twenty years: however, the investigation is far from being considered concluded.

At the beginning, as mentioned, the investigation aimed to define the nature and significance of a modest, clearly artificial little hill called Monte d’Accoddi, which, unique and isolated, still rose about 6-7 meters above the surrounding plain on a wide limestone plain.

The first excavations, directed by Ercole Contu, began in 1952 and continued until 1958.

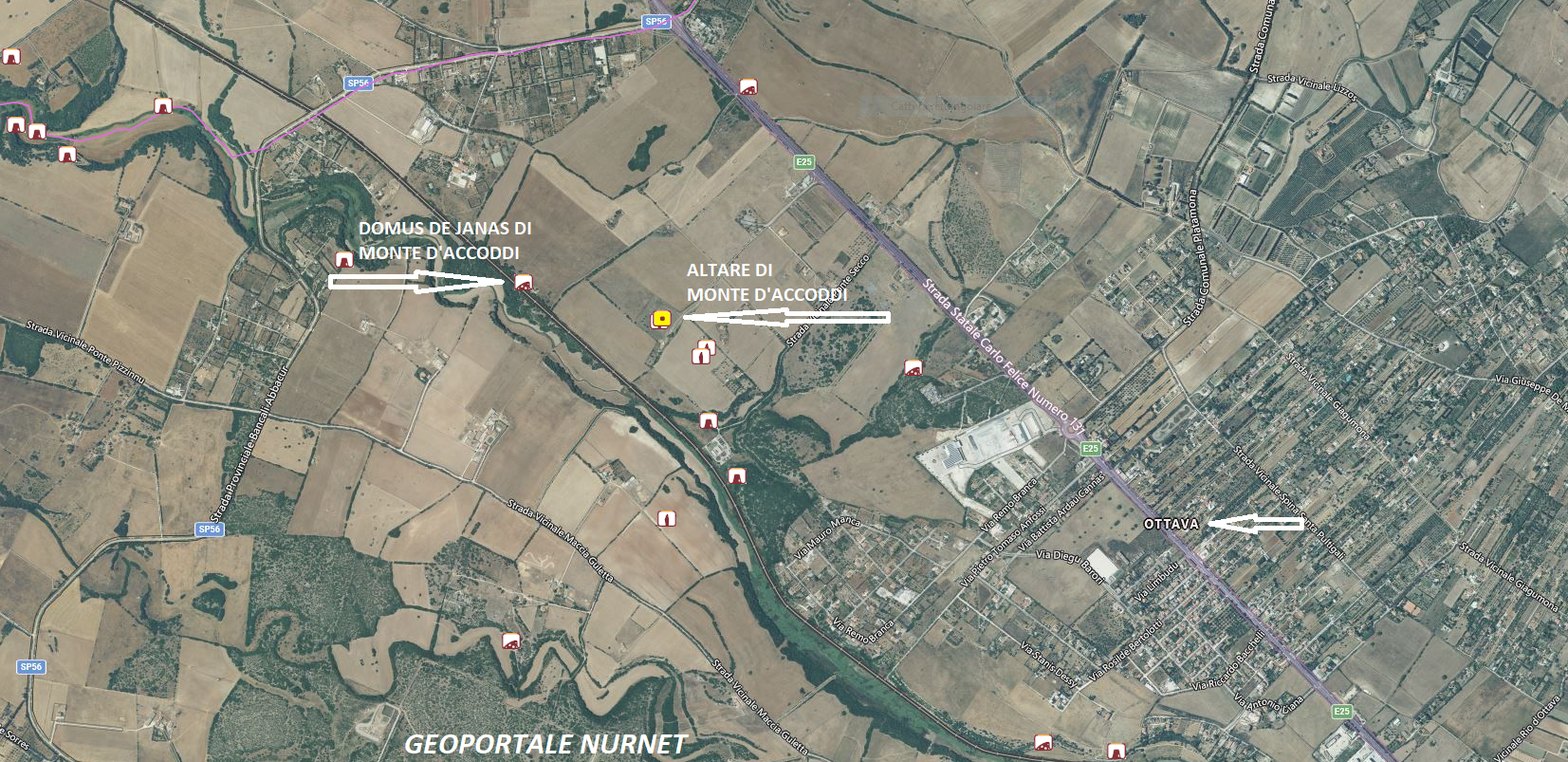

During these years, a truncated-pyramidal construction preceded by a long ramp, a menhir, two offering tables, a sector of the village, and other important cultural elements dispersed over a wide area around the sanctuary came to light.

In those same years, numerous and important necropolises and artificial grottos – hypogea known in popular tradition as “domus de janas” (houses of the fairies) – were identified, which fan out with the respective villages around the prehistoric sanctuary, indicating a densely populated territory. After about twenty years, from 1979 to 1989, the works were resumed and extended by Santo Tinè from the University of Genoa, to whom new and significant discoveries are attributed that have better clarified the function of the structure uncovered by previous excavations, reaffirming with new data the interpretation of a place of worship already proposed by Contu.

Furthermore, during these last interventions, distinct building phases were identified, and restoration and a partial and controversial restitution of the monument were realized.”…

The photos of the altar of Monte d’Accoddi are by Gianni Sirigu, Andrea Mura-Nuragando Sardegna, and Francesca Cossu. Those of the homonymous domus de janas are by Giovanni Sotgiu.