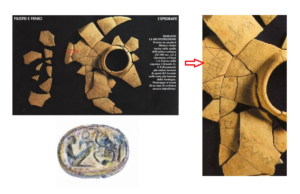

In September 2012, an interesting debate arose on the FB page of Archeologia Viva, an authoritative sector magazine, regarding the origin of the signs that appeared on the shards of an amphora found in the area of S’Arcu ‘e is Forros in Villagrande Strisaili. Among the signs was a gammed hilt dagger (indicated in the attached image with a red arrow), a typical element of Sardinian bronzetti, which could support the hypothesis that one was facing an example of nuragic writing. However, in A.V.’s post and on the photo of the amphora included in the magazine, there is instead mention of Philistine and Phoenician characteristics, excluding a priori the hypothesis of a local writing.

However, in A.V.’s post and on the photo of the amphora included in the magazine, there is instead mention of Philistine and Phoenician characteristics, excluding a priori the hypothesis of a local writing.

In fact, the article that appears in the print edition of the magazine (Sept./Oct. 2011) also includes a comment from Professor Giovanni Garbini, the leading expert on Philistine ethnicity, where it is stated that on the “Canaanite amphora dating to the 8th century B.C…. along with some Phoenician signs, the remains of an inscription in Philistine writing have been uncovered: a writing so far attested only by a few documents from Palestine and by an amulet found near Cupra Marittima in the Marche. This is a writing that the Philistines, a people of Cretan origin, used from the final centuries of the 2nd millennium B.C….”.

Garbini, noting that the Eastern presence in Sardinia was not sporadic, continues his considerations by stating that “the exceptional importance of the inscription also lies in the archaeological context (12th-7th century B.C.), which not only provides a precise dating but offers a general picture of an Eastern presence in the internal Sardinia that is not sporadic and probably continuous, as can be deduced from the presence of an Egyptianizing scarab and the so-called ‘sign of Tanit’, a Phoenician symbol that thus turns out to be much older than previously thought.” The collection of archaeological and epigraphic data from S’Arcu ‘e is Forros sheds new light on several other sites in Sardinia, such as Sant’Imbenia, near Alghero, and the nuraghe Nurdòle in Nuoro, which present similar contexts; thus, a rather unexpected historical-cultural picture of Sardinia is emerging, with a widespread Levantine presence across the island since the 13th century B.C. and particularly interested in the research and processing of metals. The Phoenician colonists who settled on the southwestern coast had been preceded by other Phoenicians who had allied with the Philistines and who, like them, lived in the nuraghi alongside the local population…

The collection of archaeological and epigraphic data from S’Arcu ‘e is Forros sheds new light on several other sites in Sardinia, such as Sant’Imbenia, near Alghero, and the nuraghe Nurdòle in Nuoro, which present similar contexts; thus, a rather unexpected historical-cultural picture of Sardinia is emerging, with a widespread Levantine presence across the island since the 13th century B.C. and particularly interested in the research and processing of metals. The Phoenician colonists who settled on the southwestern coast had been preceded by other Phoenicians who had allied with the Philistines and who, like them, lived in the nuraghi alongside the local population… Far from us to engage in sterile controversies, also because the prevailing “status” of those who read the posts published on this page is certainly that of “enthusiasts” and it would therefore be inappropriate and in some ways disrespectful to counter the claims of a luminary like Garbini and to question his certainties. However, doubts are allowed even for enthusiasts, and it is therefore legitimate to ask how one can first speak of a Philistine inscription if, according to the same scholar, Philistine writing is attested (assuming it really is) “only by a few documents from Palestine…”. Aside from the fact that the Cretan origin of the Philistines is not at all certain, considering that there are no significant traces of their presence in Crete (but this is another story).

Far from us to engage in sterile controversies, also because the prevailing “status” of those who read the posts published on this page is certainly that of “enthusiasts” and it would therefore be inappropriate and in some ways disrespectful to counter the claims of a luminary like Garbini and to question his certainties. However, doubts are allowed even for enthusiasts, and it is therefore legitimate to ask how one can first speak of a Philistine inscription if, according to the same scholar, Philistine writing is attested (assuming it really is) “only by a few documents from Palestine…”. Aside from the fact that the Cretan origin of the Philistines is not at all certain, considering that there are no significant traces of their presence in Crete (but this is another story). Why the amulet with the scarab found at the site is “Egyptianizing” and not “Egyptian” is a mystery, as is the assertion that the “sign of Tanit,” also found at S’Arcu ‘e is Forros, is certainly “Phoenician.” Professor Garbini justifies all these finds by asserting that the first “Phoenician colonists” settled in Sardinia as early as the 13th century and lived in the nuraghi alongside the Philistines and the local population.

Why the amulet with the scarab found at the site is “Egyptianizing” and not “Egyptian” is a mystery, as is the assertion that the “sign of Tanit,” also found at S’Arcu ‘e is Forros, is certainly “Phoenician.” Professor Garbini justifies all these finds by asserting that the first “Phoenician colonists” settled in Sardinia as early as the 13th century and lived in the nuraghi alongside the Philistines and the local population. The term “colonies” already raises quite a few doubts for the reasons we have expressed in other previous posts, and on which we do not believe it is necessary to dwell, but it is legitimate to wonder why, in this jumble of ethnicities that, according to Garbini, coexisted within the nuraghi, the only uneducated and non-literate populations were precisely the local ones.

The term “colonies” already raises quite a few doubts for the reasons we have expressed in other previous posts, and on which we do not believe it is necessary to dwell, but it is legitimate to wonder why, in this jumble of ethnicities that, according to Garbini, coexisted within the nuraghi, the only uneducated and non-literate populations were precisely the local ones.

In short, there are certainly no shortage of doubts, and each of us may decide whether to disagree, completely or in part, with what Garbini has stated or to accept it as a dogma upheld by the mystery of faith.

The photos of the nuragic complex S’Arcu ‘e is Forros in Villagrande Strisaili are by Nuragando, Francesca Cossu, and ArcheOgliastra Archeologia & Fotografia. The image of the amphora with writing marks found in the nuragic complex of S’Arcu ‘e is Forros in Villagrande Strisaili is taken from the aforementioned article in “Archeologia Viva.”