Understanding what functions the nuraghi fulfilled during their long period of use is probably the main and still unresolved question that often fuels debates, involving both professionals in the field and simple enthusiasts. Unraveling this mystery is fundamental, considering that it is the “nuraghe” that characterizes the Bronze Age civilization and, in other ways, the most evident “uniqueness” that characterizes the territory of the island. The opinions expressed on this matter, from the oldest to the most recent, are varied and often inconsistent with each other, but all deserving of respect. One of the most qualified hypotheses comes particularly from the archaeologist Giovanni Ugas who, in his latest substantial publication, rich in interesting observations and numerous bibliographic references, shares his personal beliefs, which reaffirm the theses that the same scholar has always supported.

From his book “Shardana e Sardegna” (Della Torre Editions-November 2016), we have extracted an interesting excerpt from the chapter titled “La struttura tribale” (for brevity, references to observations and bibliographic sources have been omitted):

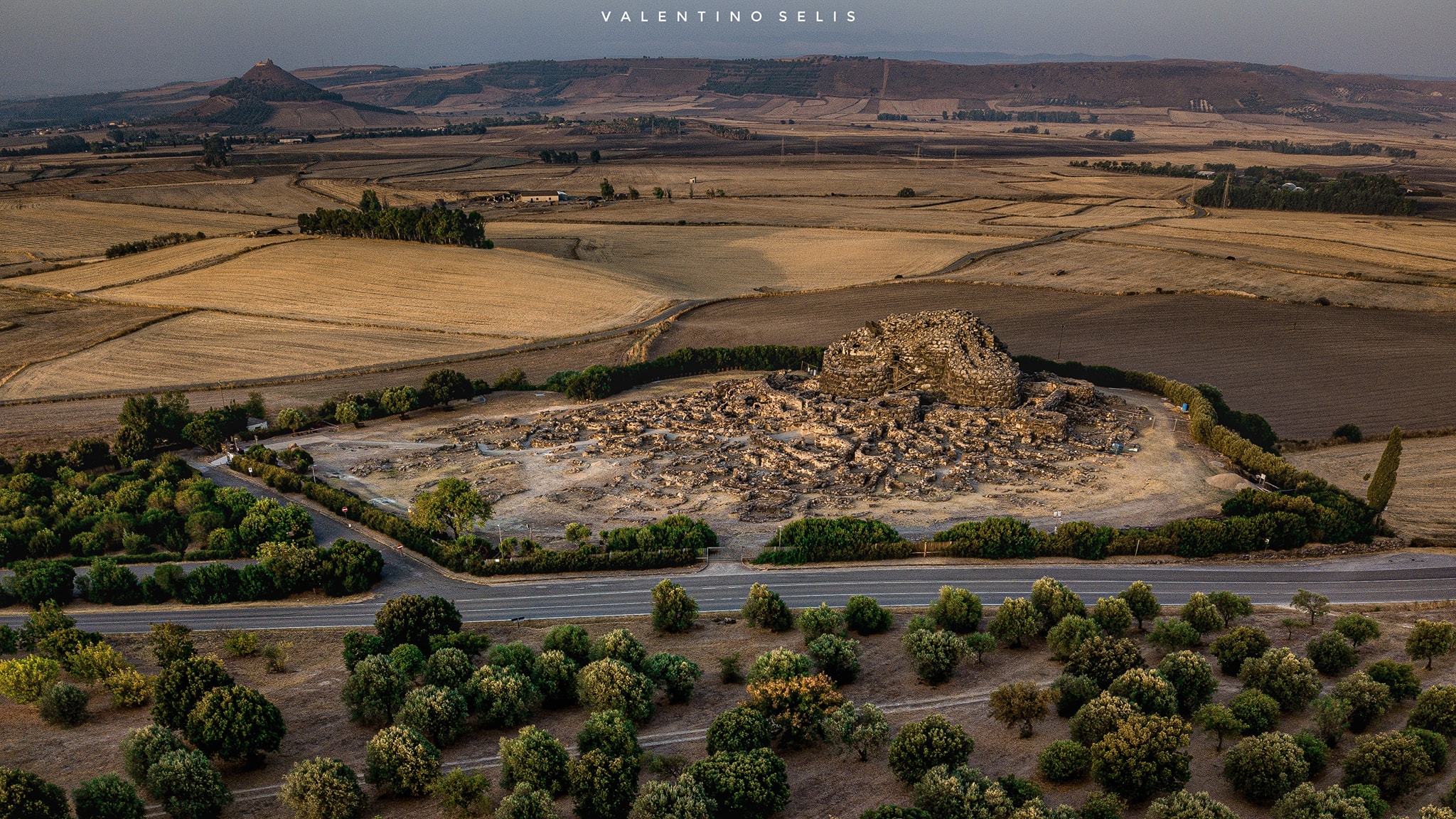

“Despite the systematic use of collective tombs leading to the assumption of patriarchal communities without social inequalities, the absence of protective walls in villages and the different articulation and grandeur of the nuraghi are signs of a hierarchized society dominated by leaders. Necessarily, the nuraghi equipped with an external wall and defended by a garrison of soldiers, that is, the palaces of the tribal chiefs, should be recognized in the palaces of the “re tespiadi” Iolaioi, that is Iliesi, as recorded by Diodorus Siculus and other Greek authors. They recount about 40, now 43 or 50 “re tespiadi” leading the Iolei, a number that tends to coincide with the number of nuraghi with external towered walls. From the 16th-14th to the 11th century, Sardinian society was centrally administered by tribal leaders, structured hierarchically. At the top of the pyramid are the chiefs or “kings” of the tribal districts residing in nuraghi equipped with external walls. A garrison of at least a hundred soldiers was necessary to ensure the defense of the large fortified proto-nuragic residences (Su Mulinu and Biriola-Dualchi), and later no less than two hundred warriors were indispensable to guarantee the security of the towered castles of the Late Bronze Age such as Su Nuraxi di Barumini, Nuraghe Arrubiu di Orroli, and S’Uraki di San Vero. The number of over seven thousand castles and single towers could be reached because, for a significant period of 600 years, from about 1600 to about 1000 BC, the same political order persisted on the island, which provided for a systematic program of settlement and progressive expansion of the tribal territory carried out through the construction of new castles and towers and the founding of other villages. The persistence of the same political model for hundreds of years also led to the strengthening of the power of tribal leaders, and probably, according to the innovations introduced in the field of funeral rituals, starting from the last decades of the 14th century, the tribal leaders transformed their initially temporary position, typical of sacred kings, into a lifelong and perhaps hereditary one, as occurred in Egypt for the pharaohs who prolonged the exercise of kingship over time, with the periodic establishment of the ritual festival “Sed” which involved the sacrifice of substitute victims and the display of a proof of valor. The location of the nuraghi throughout the island, even in the alluvial plains where large stones are absent for their construction, is another sign of an orderly and centrally coordinated settlement system. Sometimes the nuraghi in the territory of San Gavino Monreale, in the Campidanese plain, are found to be up to ten kilometers away from the source of the stone material, and their construction required not only a transport system using sleds and/or carts driven by oxen, but also the initiative of a higher authority that planned the realization of new fortified residences and made available the lithic material located even in different and distant cantonal areas from where the new nuraghe was being built. Moreover, the very existence of the three distinct peoples of the Iliesi, Balari, and Corsi implies the necessity of political bodies capable of operating at an intertribal level both in internal relations and in relations with representatives of extrainsular institutions…”

Attached are the nuraghi: Su Mulinu di Villanovafranca (ph. Bibi Pinna); Biriola di Dualchi (ph. Alex Sardegna and Marco Cocco); Su Nuraxi di Barumini (ph. Gianni Sirigu and Valentino Selis); Arrubiu di Orroli (ph. Andrea Mura-Nuragando Sardegna and Pasquale Pintori); S’Uraki di San Vero Milis (ph. Bibi Pinna and Marco Cocco).