In an interesting essay, the linguist and glottologist Massimo Pittau analyzed the location of the Garden of the Hesperides, presumably placing it in Sardinia and correctly emphasizing that it was, in any case, a legend. To Massimo Pittau’s considerations, which are reported below, I will add a note referring to the myth of Phaethon that Ovid recounts in his Metamorphoses.

I must clarify that, being a legend, it should necessarily be considered as such.

Massimo Pittau wrote: << As I prepare to address the myth of the “Garden of the Hesperides,” I find it important to preface and clarify that I consider it exclusively and entirely a “legend.” Furthermore, I intend not to analyze its symbolic or evemeristic content but to limit myself to attempting to reconstruct its geographical localization, that is, in which land of the Mediterranean it was located by the ancient Greeks at the beginning and for what geo-naturalistic circumstance. There is a first linguistic consideration to be made: >>Hesperides, in GreekHesperidesIt clearly refers to the Greek appellation.hespérha“evening” = lat.vesper. ThereforeHesperidesit properly meant “Vesperine,” that is, “Nymphs of the Evening.” In fact, they were also called “Daughters of the Night,” since the sun dies or sets in the West after the evening and towards the night. In short, the Esperidi were the “Nymphs of the evening, of the sunset, or of the West.” The function of the Esperidi was to guard, with the help of a serpent, the garden of the Gods, in which grew a tree with golden apples, a gift made by Mother Earth to Hera on the occasion of her marriage to Zeus. It should be noted that the first Greek author to mention the Esperidi is Hesiod.Theogony215 sgg.), which he calls “Daughters of the Night.” Now, since Hesiod lived around the 8th-7th centuries BC, it is clear that in the search for the origin of the myth of the Hesperides, one cannot go much further back than that period, I would think only a few decades. I mean to clarify my reference to Hesiod: I) Did he, around 700 BC, come to know of the myth of the Garden of the Hesperides from an oral tradition? In this case, we cannot ascertain anything more; II) Did he come to know of the myth from a written source? In this case, one cannot go back further than the mid-8th century BC, a period during which the Greeks began to write using the Phoenician alphabet. Modern historians of ancient Greece generally agree that the earliest settlement of the Greeks in the central Mediterranean basin, namely in the Tyrrhenian Sea, was on the island of Ischia.Pythekoûsai), in the Gulf of Naples, where they would have settled in 770 BC. Two decades later, in 750, they would have landed on the coast facing Campania, specifically at Cuma. A few decades later, in 721/720, the Greeks would have founded their colonies of Sibari on the Calabrian coast of the Gulf of Taranto, and Crotone on the Calabrian coast of the Ionian Sea. Afterwards, they would have gradually founded their colonies on the Ionian coast of Sicily. It also seems that in 580/576 Greek colonists occupied the island of Lipari, in the middle of the Tyrrhenian Sea. Therefore, regardless of some slight differences in years and decades, modern historians all agree that the Greeks entered and settled in the Tyrrhenian fundamentally in the second half of the 8th century BC. Well, for the Greeks who were now living on the coasts of the Tyrrhenian and also the Ionian, that is, in Magna Grecia, from which land was the Occident constituted at that time? There is no doubt: for them, the Occident was constituted by Sardegna. Thus, in my opinion, for this simple but also compelling consideration of a historical-geographical nature, the first localization of the myth of the Garden of the Hesperides was very likely made by the Greeks in Sardegna. This historical-geographical consideration is joined by another of a geo-naturalistic nature: it must be considered that the concept of “garden” necessarily evokes the existence of sites suitable for the cultivation of fruit-bearing plants. Well, from this point of view, Sardegna perfectly suited this need: the Island has known and still knows the cultivation of that very characteristic and also striking citrus fruit, the «cedar» (Citrus medica), whose fruit consists of a large apple of yellow color, that is, the color of gold. The Latin writer Palladio Rutilio, in his famous workAgricultural Work(IV 10, 16) celebrates the fertility of the territory of Neapolis (on the southern shore of the Gulf of Oristano), where he owned lands and successfully cultivated the cedar plant. In this same line of thought, these Sardinian toponyms and hydronyms speak very clearly:Chiterru(fraction of Buddusò and surname in Budoni and Padru), which probably corresponds to the Etruscan gentilice.Cethurna, Ceturnaand also to ancient Italiancederno“cedar” (previously suggested as of Etruscan origin);Cedrino, the river of Baronia;Villacidro(localmenteBiddaxírdu, Biddexídru = Bidd’ ‘e Xídru)= “Villa of the cedars”(chídru, cídru)“cedar” from Latin.citrus; sing., but with collective value). Currently, the cedar is successfully cultivated particularly on the eastern coast of the Island, less exposed to the maestrale, right in front of Magna Graecia, in the valleys of Baronia, Ogliastra around Tortolì, and Flumendosa in Sarrabus. It should be noted that, for the purpose of the exegesis of the “Giardino delle Esperidi,” some authors have referred to the “orange gardens.” However, this comparison should be rejected both because oranges have a red color and not yellow, and therefore do not appear to be the color of gold, and also because, as my colleague and friend Ignazio Camarda, a botanist at the University of Sassari, has taught me, the cultivation of oranges arrived in the central Mediterranean much later than the classical era. Finally, I would like to point out that in the myth of the “Giardino delle Esperidi,” the one aboutHerculesHe would indeed have gone to the Hesperides to search for the apples of immortality. Moreover, he would have recovered the rams of the Hesperides, stolen from them by brigands (here there was a play on words, given that Greek…melonIt means both “apple” and “ram”). That said, it is worth noting that the presence of the mythical Hercules or Heracles is widely documented, also identified with the PhoenicianMelqart,even in ancient Sardinia: there are some locations named in his honor, for example theIsland of Hercules= Asinara (Ptolemy, Pliny, Marcianus Capella), the bus stationto Herculesquoted by the Roman “Itinerary of Antoninus” (83, 4) amongTibula(Castelsardo) andTurris(Porto Torres) and that I locate atSaint Michael of Plaiano(Sassari). But particular importance for my purpose is the arrival (entirely mythical?) in Sardinia, led by Iolaus, of the fifty Tespies, sons of Heracles, whom he had with as many daughters of Thespis (Pausanias X 17). For these three stated reasons, one historical-geographical, the other geo-naturalistic, and the third mythological, it seems to me that the hypothesis that the first localization the Greeks made of the myth of the “Garden of the Hesperides” was indeed in Sardinia is very plausible. However, it later happened that, as the maritime horizon of the Greeks expanded, especially after the foundation of their great colony of Marseille in 600 BC and its subcolonies, the Greeks also shifted their “West” and consequently the localization of the myth of the “Garden of the Hesperides.” They moved it to the Iberian Peninsula and even later to the end of the northern coast of Africa, towards the Atlas mountain; so much so that even the parentage of the Hesperides changed several times, eventually being referred to as the daughters of the giant Atlas.

As mentioned in the preamble, I would like to add a note to what Professor Pittau wrote, referring to the myth of Phaëthon, son of Phoebus/Apollo, often identified with the solar god Helios. Phaëthon, having obtained permission from his father to drive the “horses of the sun” across the celestial dome, lost control of them. The horses, wild and galloping madly, “caused a disaster” (forgive the extreme brevity) in the sky and on earth. Whereupon Zeus, furious, struck him down with a lightning bolt. What happened immediately afterward is recounted by Ovid in his “Metamorphoses”, writing that “Phaëton per caelum praecipitat et in Eridanum cadit ubi Naides Hespiriae in tumulo corpus condunt” (Phaëthon falls from the sky and lands in the Eridanus, where the Naiads of Hesperia bury his body in a tomb). If we consider that according to legend, the horses of Helios grazed in the garden of the Hesperides at the end of each day, and that the Hesperides were daughters of Phorcys, the mythological king of Sardinia and Corsica, why not think that the “spot” described by Ovid was precisely Sardinia, confirming what Professor Pittau hypothesized?

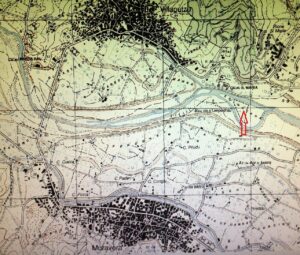

However, it remains to be understood what relationship there could have been between our island and the Eridanus. A river that according to Virgil was located in those “infernal” places notoriously in the distant west and sometimes identified with the Po, sometimes with the Rhône. Well, on the eastern coast of Sarrabus, near the mouth of the Flumendosa, there is a plain called “Eringiana,” near which was located the ancient port of Sarcapos. The similarity between the toponyms Eridanus and Eringiana is evident, but it can also be observed that the territory of Sarrabus is notoriously renowned for citrus production – including the cedar.Citrus medica) cited by Professor Pittau – and it is located to the west of the Tyrrhenian coasts where, as noted by Pittau himself, the Greeks had settled.

I conclude my note here, apologizing to anyone who might be struck by exanthematous reactions at the mere mention of the word “myth.” But the history of Sardinia is filled with place names and legendary references that stimulate the imagination but also provoke some reflection… which is not a bad thing!

In the images: the fall of Phaethon in a painting by Hans Von Aachen and the plain of Eringiana at the mouth of the Flumendosa.