The yoke, an ancient device used for animal traction but also to indicate the same animals to which it is applied, generally a pair of oxen, is called “Su Ju”, “Su Juale”, “Su Juvale” or in other similar ways in the Sardinian language. The one made up of two Modicano Sardinian oxen traditionally carries the carriage of S.Efisio during the namesake festival, and the older generations will probably remember ziu Antoni, who raised a double pair of oxen (one as a backup for the other), used for transporting the saint. The older “Su Ju” was made up of the pair “Bollemu” and “Po Tui”, names that underscored the affection between the two animals, while the younger two were called “Mancai Provisi” and “Non Ci’Arrenescisi” to humorously highlight that they would hardly measure up to the more mature pair. Aside from these amusing curiosities, “Su Ju”, in ancient Sardinian tradition, had another use. Dolores Turchi writes in this regard, referencing some testimonies, that to facilitate the passing to a better life of suffering and agonizing people, “the greatest remedy was considered by all, as Angius states, the yoke of a plow or a cart. This tool was supposed to have a special significance. During some of my research done several years ago in numerous villages, I found that almost all older people were aware of this practice. They also specified that the yoke should be treated with ‘religious’ respect and should never be burned. According to some, prolonged agony was due precisely to the fact that the dying person had stained their life with the crime of having burned a yoke. In Urzulei, it was said: ‘If the yoke is old and unusable, it is placed in a corner, behind the door, and left there. It should never be put to the fire. In the past, when a person struggled to die, the yoke was placed under their head.’ The same assertion is made in Orgosolo, Benetutti, Bitti, Oliena, Orotelli, Mamoiada, Dorgali. In Sarule, it is added: ‘If an individual struggled for a long time between life and death, the yoke, su juvale, was taken, the dying person was marked, made to kiss the tool, which was then placed under their head.’ When the person died, su juvale was placed under the bed with two crossed sticks. The same statement is made in Ollolai. The same custom also existed in Baronia. In Siniscola, it is specified: ‘Su juale was considered a sacred object… It was said that a man who threw away or burned the wood belonging to a yoke, at the moment of death suffered greatly and had a long agony. When it was seen that a man was struggling to die, they made him kiss the yoke and said prayers to free him from the sacrilege he might have committed during his life by burning the wood of a yoke. Even today, many people, if they see a yoke thrown in the countryside, do not touch it, for fear of committing sacrilege.’ Another reliable testimony comes from the church world: ‘When I was a parish priest in Sìndia, it happened several times, while giving the sacrament of extreme unction, to see under the pillow of some dying person the yoke of oxen. I would reprimand the women who did this, but they were convinced that with that tool around the neck, the agonizing person would not suffer long. I have seen this done in Sedilo as well.’ In many villages, it is stated that su juvale was also used to facilitate childbirth and to protect the baby from the surbiles. In this case, it was placed under the bed or behind the door (Ollolai, Orgosolo, Benetutti, Oliena, Bitti, Tanaunella). Evidently, it was also attributed protective powers, but it is clear that this tool presided over the birth and death of individuals. The effectiveness of the yoke in avoiding long agony is also evident through some popular sayings. Ferraro collected this riddle in the last century, in Siniscola: ‘Duos montes paris paris, / duas cannas treme treme, / si lu pones in cabizza, / prus lestru ti nde moris’ (two mountains just like that, two reeds that tremble, if you put it under your head, you die more quickly). Obviously, the answer was: su juale. Ferraro also reports: ‘This is a superstition of the peasants from many places in Sardinia, namely that those who have a long agony cannot die unless they are placed under their head a juale.’ Regarding what has been stated so far, I observe that the practice of placing the yoke under the head of the dying is analogous to that used in ancient Egypt, where an object shaped like a crescent called “ueres” was used, employed also by the living but mainly as support for the heads of the deceased. In this latter case, the material used for its construction, aside from wood, included ivory, alabaster, terracotta, and hard stones. On the pages of the Treccani Encyclopedia, it is read in particular that “the close link between the headrest and the head of the sleeper, and therefore of the deceased, gives the object a magical value within the realm of funerary beliefs, as seen in the Coffin Texts of the Middle Kingdom and subsequently in the Book of the Dead; it is no coincidence that starting from the XVIII dynasty, the shape of the headrest becomes part of the typology of funerary amulets, sometimes accompanied by specific magical formulas.” The Egyptologist Maria Carmela Betrò writes in turn: “Bound as it was to the unsettling nocturnal world, the object destined to support the head, more susceptible than other parts of the body to the attacks of malevolent forces and therefore more in need of protection, was often decorated with apotropaic deities, traditionally associated with sleep and the benevolent watch over the sleepers: the dwarf Bes and the hippopotamus goddess Toeri foremost” (M. Carmela Betrò: “Geroglifici”). Furthermore, the Sardinian term Ju, Juale or Juvale is typically derived from the Latin jugum (Greek ζυγόν). As a point of curiosity (not being a glottologist, I do not delve into fields that do not belong to me), in hieroglyphic terms, the bovines were referred to as “iwa” (jua). A name clearly similar to the term ju or juale with which the yoke is indicated in Sardinian.

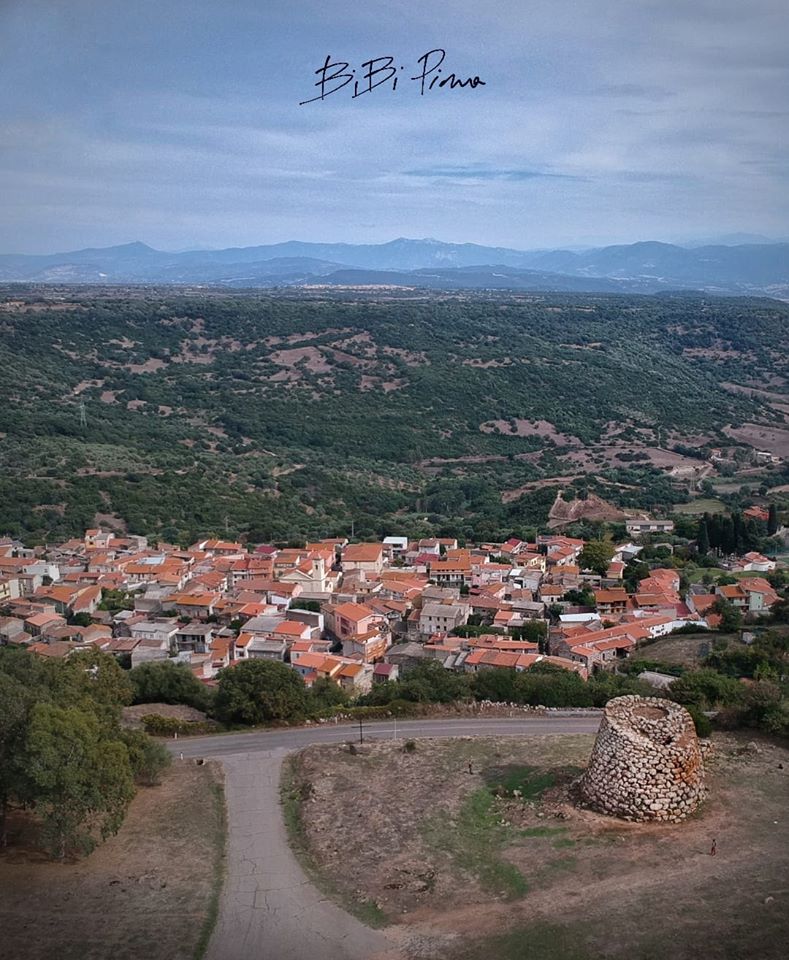

Attached: The nuraghe Sa Jua of Aidomaggiore (photos by Nicola Castangia, Bibi Pinna, Alex Meloni, and Vittorio Pirozzi); the yoke of oxen transporting the statue of Sant’Efisio during the namesake festival (photo by the author); a yoke (photo from Wikipedia)